|

POP WALL ALPHABET

a transmedia work for sound compositions, algorithmically generated texts and images. 2011-15 Pop Wall Alphabet consists of 26 parts that comprise more than 4.5 hours of sound compositions, 26 algorithmically generated texts and 26 images. Each of the 26 sections deals with one particular Album from pop history from the past almost 50 years. The first letter of the name of the band or singer stands for a letter in the alphabet, together the 26 sections are forming the entire English alphabet: Abba for letter A, Beastie Boys for the letter B, Chemical Brothers for the letter C and so on. The Sound Composition is based on superimpositions of all songs from a particular album. Furthermore, spectral freezes of each of the songs are used in order to create a variety of sonic condensations. Every section starts with maximum density, with the spectral freeze that fades out quickly and leaves all songs superimposed. These songs then drop out successively depending on their individual duration. During this process I always found it very interesting how the sonic texture in the very beginning first sounded abstract but then gradually blended into a dense sound where I could first recognize the genre of the superimposed tracks, then the band or singer, and eventually the individual song. When the last and longest song remains, the second section of the piece begins, where the spectral freezes of the individual songs blend into each other in the reverse order as they dropped out. Here, I again discovered a fascinating listening phenomenon. Although the spectral freezes are practically noise with a particular filtering, I often kept hearing melodies, harmonic progressions or even rhythms in it, although they were not there. My brain was playing tricks on me and what I experienced was acoustic pareidolia. However, pop is not only about sound. Songs contain lyrics. I decided to apply a process to the lyrics of each album that corresponds to the first part of my musical renditions. So it starts with noise and gradually the texture thins out and we start to recognize familiar things. I applied this to text by writing a program that would first take a single letter from each text that belong to the songs of a pop album, then the second letter, the third etc.. As the program progresses through the texts it starts to copy larger fragments: two letters instead of one, then three and so on. The result is something that is very similar to the music. At first the text looks completely random – noise you could say –, but later on you at first start to recognize fragments of words, then complete words, then fragments of sentences and eventually an intact succession of words, which – just like with the music – happens to come from the longest text of all. The entire work is a study of perception; on how the mind transitions from perceiving abstract to familiar materials, and how even non-existent time-variant phenomena can be “imprinted” on static noise. Pop Wall Alphabet: an Introduction by SIMON CUMMINGS

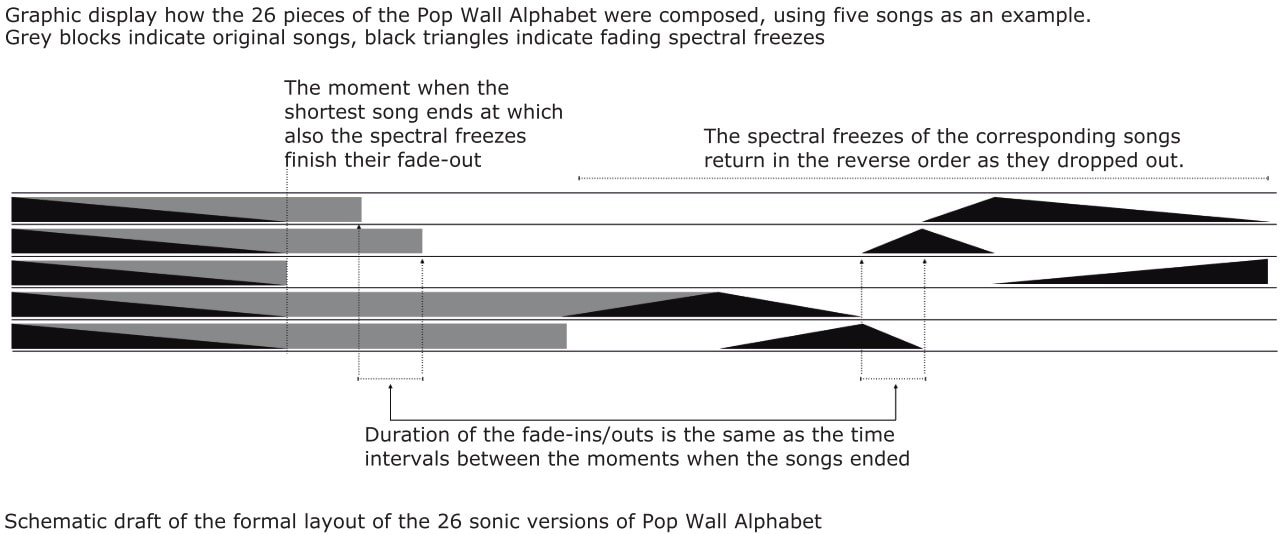

It doesn’t take much of an imaginative leap to regard noise, with respect to information, as a disruption and/or an impediment. Indeed, the very word ‘noise’ has long been so dogged with such aesthetic associations and value judgement corollaries that it has effectively become conceptually onomatopoeic, a connotative example of itself. In many if not most minds, noise represents something blank and inhuman, a random wall of confusion at odds with both order and imagination. At first glance, Marko Ciciliani appears to be tapping into that sensibility, employing the word ‘wall’ centrally in his title. But Ciciliani’s ‘wall’ is subtle and multi-faceted, not simply exploring archetypal walls of sound. A wall, after all, is a construction, and in Pop Wall Alphabet it is individual albums, their tracks, lyrics and artwork, that constitute its bricks. The title is in fact all about construction, a three-word, functional summary of the work’s materials (pop), methodology (wall) and structure (alphabet). Ciciliani’s theme, then, is Pop, in all its multifarious, genre-defining and -defying forms and idioms. More specifically, the source material is 26 pop albums released between 1970 and 2014, a diverse selection including Abba, Nirvana, Eminem and ZZ Top. His primary interest is two-fold, aesthetic and technical, encompassing an “investigation of ‘the sound’ which has become a central but nevertheless evasive and intangible criterion in pop production, giving it an almost mythical quality”,[1] alongside “a fascination with the changes in perception that occur when familiar materials are condensed and concentrated, and in observing how well-known material gradually becomes alienated and eventually unrecognisable as it is superimposed in an increasing number of layers”.[2] With these in mind, the methodology of Cicilani’s aesthetic investigation is similarly bifurcated. The first, more straightforward approach is to regard the album as a whole, superimposing all its tracks on top of each other simultaneously to create a dense texture amalgamating anywhere between eight and 20 songs. The second treats each track individually, analysing it and then randomising the resultant data; although all the original frequencies appear at the correct amplitude, their randomisation creates a ‘spectral freeze’, a re-synthesised rendition of the song in which its essence is captured in an apparently static block (or wall) of filtered noise. Fig1: Schematic draft of the formal layout of the 26 sonic versions of Pop Wall Alphabet

Cicilani juxtaposes these two types of material in order to create a single piece based on each album. They fall into two parts (dividing the piece exactly in half), the first of which features all the tracks superimposed. In addition, all of the spectral freezes are also played simultaneously at the start, immediately fading out, the duration of their fade being equal to that of the shortest track on the album. The superimposed tracks continue, dropping out as they each come to end. As soon as there is just one track remaining, part two begins, comprising the spectral freezes of each track, played one at a time in reverse order of when their tracks dropped out earlier, the fades in/out equalling the time intervals between these moments of drop-out. This latter half therefore consists of a sequence of shifting walls of bandwidth, each a microcosm of the frequencies, timbres, amplitudes and every other aspect of the original track, together becoming a densely compacted noise tapestry of the album in its entirety. A visualisation of this can be seen in the diagram above. A technical description such as this might give the impression that Pop Wall Alphabet is a work all about process, yet Ciciliani’s methodology – formulated gradually through trial and error – is working towards very much more insightful ends, ends that are both strikingly immediate and intimately personal. However, it must be acknowledged at the outset that Pop Wall Alphabet is a daunting entity; from a global perspective it lasts four-and-a-half hours, much of which comprises noise in a plethora of hues and colourations. And even from a local perspective, simply regarding one of its 26 movements, we are confronted by roughly ten minutes of non-stop, highly-wrought turmoil, a gradually more concrete first half answered by a kaleidoscope of abstract blasts in its second. This acknowledgement is a way of making a much simpler point: Pop Wall Alphabet – as outlined above – makes minimal sense or impact on paper. The description above explains how and of what it is structured, but says nothing at all about how it works. Ciciliani is seeking, in part, to capture and expose the ‘sound’ of individual groups and artists, and to this end, Pop Wall Alphabet must above all be heard – an act that requires nothing less than immersion – in order for its aims to crystallise and ultimately be fulfilled. Any response originates in one’s individual relationship with stimuli, which in the case of Pop Wall Alphabet is influenced by many things but perhaps chiefly by familiarity. In choosing sources from the world of pop music, Ciciliani has consciously embraced material that is likely to be known – at least subliminally or anecdotally – by a substantial proportion of his audience. This potential existing relationship with the work’s source materials introduces aspects of memory and nostalgia to the listening experience, creating what Cicilani describes as an ‘emotional subtext’. This subtext, unique to each listener, is critical in the way the work is perceived. |

While disorientation and bewilderment initially reign within each particular piece – being bombarded simultaneously by all the album’s tracks in addition to their freezes, the only point when the album’s entire contents are heard at once – this wall of abstraction swiftly yields to an increasingly transparent texture as the freezes fade and, eventually, tracks finish and drop out. But even before this, that massive opening sonic salvo itself has already begun to distil and clarify something generalised about the music in its particular agglomeration of bandwidths. Abba’s, for example, encompasses a very wide frequency range, while Kraftwerk’s features high frequencies less prominently. Beastie Boys’, by contrast, projects high and low bands most strongly, a somewhat ‘in your face’ noise wall redolent of the band’s aggressive style, while ZZ Top’s heavy mid-range instantly brings to mind a frantic guitar tremolo, encapsulating their distinctive soundworld.

As the piece progresses, certain details make themselves heard with surprising clarity: Michael Jackson’s vocal gymnastics, Oval’s pervasive shuffling glitches and bass throbs, Queen’s multi-layered group textures and rhapsodically dramatic structures, LFO’s overtly electronic bleeps and beats. This is Pop Wall Alphabet’s second layer of distillation, a kind of panning for gold where nuggets of information – containing the music’s most prevalent aspects and thereby embodying the defining hallmarks and fingerprints of each album – are revealed and teased to the surface as a simple consequent of the tracks’ superimposition. What lies beneath is just as revealing, however. Under the surface clatter in many of the pieces can be heard a sort of ‘cloud of consonance’, a dense accumulation of each song’s tonality focussed in a hovering, shifting chord. Albums with less emphasis on conventional songs differ markedly; Kraftwerk’s underlying texture sounds like a lab filled with computers caught up in their own analogue reveries; Eminem’s is an itchy network of frantic lyric and beat fragments tripping over each other; Nirvana have a seemingly razor-edged backdrop, while Beastie Boys, fittingly, seem to be in the midst of the world’s biggest punch-up. Dynamic range – or lack of it – is another key feature of these background sonic masses; Pink Floyd’s is arguably the most intricate, a filigree of components in a distinct soundstage, whereas more contemporary artists like Lady Gaga and Rihanna, whose albums are hapless sacrificial victims of the ‘loudness war’, display a hard, brutalist soundscape essentially indistinct from one other. The final and most complex layer of clarification begins at the mid-point of each piece, with the introduction of the sequence of spectral freezes. It may seem nonsensical to regard such granite-like walls of frozen sound – music at its most architectural! – as either complex or clarifying, but they are demonstrably both. Their complexity lies less in the obvious fact that they embody a large amount of (randomised) musical data than in their ontology, comprising both a real and an imaginary component. The former, that which is actually heard, is in a sense not dissimilar from the textural undercurrents permeating the superimpositions heard before. The more timbrally abrasive examples result in similarly hard-edged sheets of noise, while those imbued with a more overt harmonic sensibility create a kind of quasi-Schenkerian ‘Ursatz’, their underlying tonality simplified into a single rich, resonant chord (an obvious example occurring in the final U2 freeze, locked on a convoluted but unmistakeable chord of D major, the tonality of shortest track ‘In God’s Country’). The imaginary component of these freezes is harder to describe, because it is largely dependent on the mind of each listener. Put generally, the wall of noise in each freeze, informed by the previously-heard superimposed tracks – which, although with difficulty, can to an extent be individually perceived via the ‘cocktail party effect’ (the brain’s ability to focus on a single auditory source amidst many others) – and reinforced by any existing knowledge of the music, produces instances of pareidolia, an imagined sense of order or meaning when confronted by random information. Ranging from a vague notion of movement to the perception that one is actually hearing phrases and snippets from the original songs, this entirely illusory response is a product of the ‘emotional subtext’ mentioned above; precisely what one ‘hears’ is an intimate, emergent property from the swirl (or noise) of passive/active promptings within each listener’s mind and memories. Pop music, for all its ostensible emphasis on sound, places just as much if not more significance on the extra-musical trappings with which it is presented and marketed. While one of his primary interests is in the ‘sound’ that serves to define a pop album, Ciciliani’s survey extends to both the lyrics of the songs and also the album artwork. These tangential explorations are largely analogous to the sonic superimpositions. With the lyrics, in each case Ciciliani moves through the different songs’ texts simultaneously in increasing quantities, beginning with just a single character. This results in an initial ‘blast’ of capital letters, followed by an extended episode of incoherent textual noise which gradually reveals lyric content with more and more clarity, lines from individual songs eventually becoming fully comprehensible. Albums with no verbal content, such as Oval’s Systemisch, are omitted, while those of a more garrulous lyrical disposition – Eminem being the most obvious example – produce vast tracts of avant-garde verbiage. These new texts are fascinating in the way they resemble a concerted effort towards expression, from inchoate utterances to lengthy outbursts of often highly personal (or at least ersatz) sentiment. Ciciliani’s approach with the visuals is to superimpose all 26 album artworks upon each other, using a digital colour-mixing method that focuses on absolute differences between RGB pixel values. Moving through the alphabet, Ciciliani uses the preceding album as a colour filter for each successive artwork, while the rest are visible beneath. The result is a fascinating interpenetration of information and colour, fragments of image and text bleeding through the visual noise as isolated points of past, present and future signification. Marko Ciciliani’s Pop Wall Alphabet acts both as a paean to the bizarre mix of triumph and disaster that is and has always been pop, as well as a celebration of the technicolor brilliance and potential of noise. On the one hand a searching scrutiny of pop’s machinations and motives, it discovers dazzling new quantities and qualities of beauty that coruscate out from its convoluted findings. It clarifies key ingredients within its source materials, bringing them to the surface while peering deeply and at length into the swirling, nebulous depths beneath. Regarded in its transmedia entirety, it is that most rare and exciting of artistic creations, simultaneously affording a penetrating examination of its subject matter from a hitherto unimagined and certainly unexplored perspective, while at the same time offering a hugely rewarding, even intoxicating experience on its own terms. If pop, in its noblest moments, aspires to anything, it is to glory, even ecstasy; both are found in epic amounts throughout Pop Wall Alphabet. [1] M. Ciciliani, ‘Pop Wall Alphabet’ programme note, Noise In And As Music Conference Booklet, University of Huddersfield, 2013 [2] 2 M. Ciciliani, ‘Molding the Pop Ghost’ in A. Cassidy and A.Einbond (editors): Noise In And As Music, (Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield Press, 2013) Back to Installation & Sound Art

|