|

WHY FRETS? - REQUIEM FOR THE ELECTRIC GUITAR

a performance-lecture COMPLETE TEXT OF THE PERFORMANCE-LECTURE Original Story: Marko Ciciliani Writers: Marko Ciciliani & Nicolas Trépanier PART I

1. Introduction A hundred and fifty years ago, US-American inventor Georges Beauchamp assembled an odd looking object, a string instrument that he nicknamed “the frying pan”. The Rickenbacher A-22, as it was officially named, was released in 1933 and made history as the very first electric guitar ever produced, an instrument that shaped popular music until its demise a few decades ago. The crucial technology that made Beauchamp’s design revolutionary was the pickup. The basic working principle of the electric guitar is this electromagnetic sensor, which uses induction to react to the movement of a vibrating metallic object that enters its magnetic field by generating an electric current. The electric current it generates can then be turned into sound by means of amplification. This is why electric guitars only use steel strings, since nylon or gut strings would not produce any induction at all. But was this ground-breaking innovation truly Beauchamp’s own creation? My recent research has uncovered striking new evidence that shows without a doubt that the electromagnetic pickup was in fact created a full century earlier by a British engineer of German origin named Sieglinde Stern (1798-1859). The documents I have found strongly suggest that Beauchamp indeed knew of this technology, which he appropriated and economically exploited. In this lecture, I will present the story of Sieglinde Stern, and discuss the reasons that prevented her until now from getting the recognition she deserves as one of the great innovators in the history of music technology. 2. SIEGLINDE'S BACKGROUND

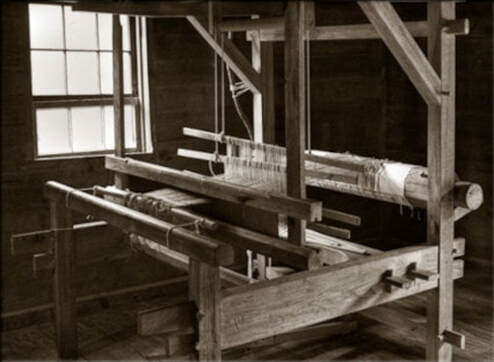

My earlier research centered on the early activities of the Royal Institution of Great Britain, founded in 1799, and specifically how the institution reached out to the general population with a series of public lectures on science. In the course of this project, I repeatedly came across the name of a woman named Sieglinde Stern, who stood out as a rare female in an overwhelmingly male audience. As it turned out, Stern was part of an important industrialist family whose archives are still extant today, and include among many others several volumes of her diaries and over 200 of her letters. The Sterns were a Jewish family of German origins. A few years before Sieglinde’s birth, they migrated from Frankfurt to London where her father became an important industrialist. His business ventures involved the textile industry, one of the main driving forces behind Britain's Industrial Revolution. Meanwhile Sieglinde's mother came from a family of weavers and was a master in this craft. Drawing from this expertise, she taught Sieglinde from an early age how to operate a hand loom, using both standard and advanced techniques. As any daughter of a well-to-do family at the time, Sieglinde was also educated in music, becoming a proficient amateur violinist. However, her diaries leave no doubt that that the subjects that truly captured her attention were modern science and new technologies. This interest in science and technology was spurred by the many visits she made to her father’s factory. Although her father took her and her siblings there primarily for her brother as he expected him to eventually take over the business, Sieglinde was deeply impressed by the power and capability of the machineries. A note from her diary from when she was only 14 years old, offers a good example of the impression this made on her: "To think these machines perform the same labor as the weaving techniques mother has shown me! The speed! The precision! Truly, if these power looms can work so fast and so well, can they not bring good fortune to society as a whole in countless other ways?" It is important to note that the textile industry was one of the most developed sectors of Britain’s early industrialization, and as such regularly generated new inventions. However, it also created horrific conditions for its workers, with long working days, low salaries and frequent accidents. There is no doubt that Sieglinde was especially fascinated by the way weaving could integrate the ancient tradition that she had learned and mastered from her mother with entirely new, cutting edge technology that, under the leadership of men like her own father, were rapidly transforming the society in which she lived. Such combination of tradition and innovation, as well as her familiarity and expertise in these two modes of thinking, was crucial in the series of events that led her to invent the electromagnetic pickup. 3. SIEGLINDE'S ADOLESCENCE AND EXPERIENCE WITH SCIENCE

Sieglinde’s interest in science led her to attend, as a teenager, the lectures offered at the relatively newly founded Royal Institution of Great Britain. There she was able to hear, among others, Michael Faraday, who was about to become one of the organization’s most prominent members. It is also while attending these lectures that she met and became romantically involved with Charles Anderson who, after a short military career, was soon to become Michael Faraday's assistant. In 1831 - in the meantime Sieglinde Stern has taken a managing position at her father's factory - Faraday spent a little over three months in an intense series of experiments at the Royal Institution that eventually led to his discoveries in the field of induction. Charles Anderson assisted him throughout this period. As the experiments grew in complexity, it became clear that Faraday needed an additional assistant, a position for which Anderson suggested Sieglinde Stern. At first sceptical at the idea of letting a woman into his lab, Faraday nevertheless trusted Anderson’s reassurances and praise for the understanding of physics that Sieglinde had developed both through individual study and by attending the lectures at the Royal Institution. Faraday was not disappointed. Sieglinde very quickly picked up on his experiments, as we can see in this excerpt from her diary, dated November 2nd, 1831: "F.‘s is quite right, magnetism and electricity are connected, just like Oersted and Arago have argued. Further, we have shown very well that electricity can create magnetic forces. But how shall we prove that the reverse relationship also obtains? F. seems certain he can convert magnetism into electricity? Think of the marvels that should arise, if motion and magnetism can generate electricity!" Sieglinde also described in great detail the individual steps through which Faraday eventually reached his goals. Here is a note describing an experiment from a few weeks later, November 29: “First we wound 26 feet of copper wire round a wooden cylinder as a helix. Next a second copper wire was wound on top of this. This process was repeated till we had 12 coils of wire, all insulated from each other. We then connected the free ends of all the even coils to compose one continuous length and likewise with the odd coils. Now with two helices, F. connected one end to a galvanometer and the other to a voltaic pile. And yet, this didn’t work. It took two more days of experimentation with longer wires of diverse materials. But then the miracle finally happened: just like Faraday had expected, when switching on the pile the galvanic needle danced to one side. When disconnected it, it gently returned to its place. Spectacular!" The professional relationship with Faraday ended after this phase of experimentation on induction, and the sources I consulted do not mention him again. Yet less than two years later she put the principle of induction to use in a different way when she invented the first electromagnetic pickup, which she used in the first electric string instrument. The innovative character of Stern’s design came from the fact that she abandoned the shape of the magnetic ring, opting instead for a magnetic rod, which created magnetic fields in its vertical extensions. This was particularly suitable for picking up subtle motions of small metallic objects as such of a metal string. It seems obvious that her familiarity with weaving is what allowed Stern to develop this device. More specifically, the so-called flying shuttle appears to have served as a design template for her pickup. Invented by John Kay in 1733, the flying shuttle was a crucial technology that allowed for the acceleration of the weaving process and its industrialization. The flying shuttle dispenses the warp while being thrown across the loom. What makes this possible is that the flying shuttle contains a spool - called the bobbin which includes the so-called pirn – from which the yarn unwinds as it travels from one side of the loom to the other. Stern’s design of the pickup was modeled on the rod, the key difference residing in the materials used. In the flying shuttle used in weaving, the pirn is usually made of wood or metal, and the thread is of cotton or wool. Her innovation was to replace the rod with a magnetic metal, and the yarn with shielded copper wire, resulting in an electromagnetic pickup. Although relatively simple, this design would have been difficult to imagine without Sieglinde’s expertise in both weaving and physics. Although in retrospect the invention of the magnetic pickup appears to us as a massively important development in music technology, it did not result in fame and fortune for Sieglinde Stern. Rather than obtaining a patent and exploiting it economically, she put her invention to use in a much more private, and even secretive, environment. PART II

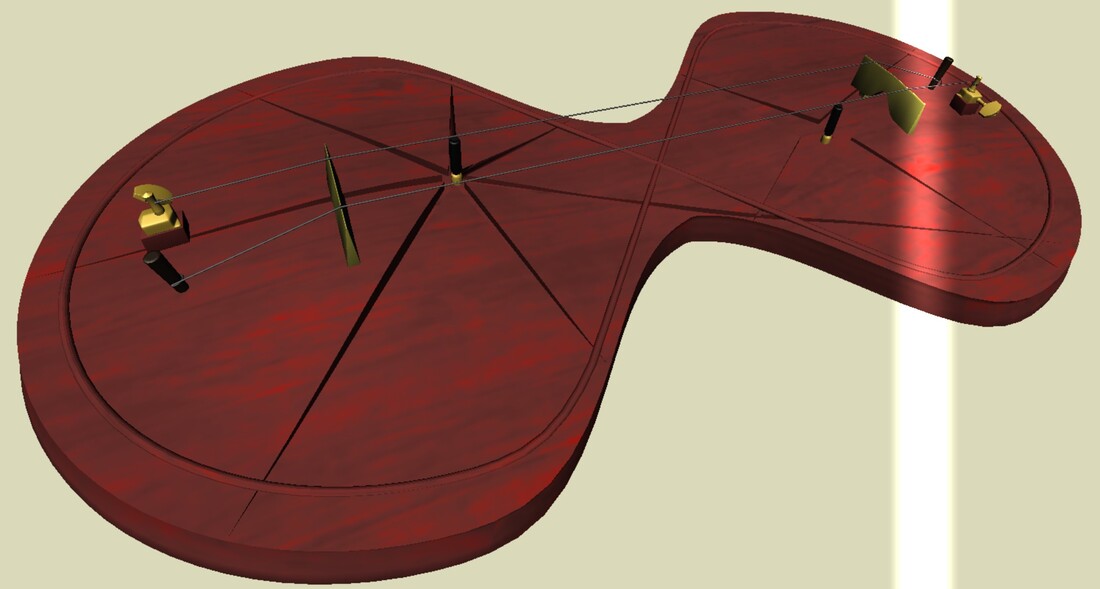

4. SISTERS OF THE HARMONIC CONSTELLATION Early nineteenth-century England was teeming with secret societies. Sieglinde’s father, for example, was a member of one of the most prominent of these organizations, the Freemasons. In my book Sharing is Daring: the propagation of information and knowledge in 19th Century Britain, I have examined the multiple ways in which secret societies participated in the spread of scientific knowledge among the English population. Sieglinde Stern was herself a member of another such group, called the SISTERS OF THE HARMONIC CONSTELLATION. As its name suggest, this was an exclusively female organization, and it brought together women that had a thirst for knowledge and debate on subjects ranging from philosophy to physics. The group had been created a few decades earlier by Mary Taylor. Taylor herself was married to prominent classicist Thomas Taylor, whose famous translations of Plotinus and teachings in neo-platonism became central to the discussions of the Sisters of the Harmonic Constellation. This interest in neo-platonism brought the Sisters to collectively study Pythagoras’ systems of harmony, from which the group took its name. For Pythagoras, the concept of harmony characterizes all aspects of our existence, from the way the human soul is constructed to the planetary system. However, the SISTERS OF THE HARMONIC CONSTELLATION disagreed with some aspects of Pythagorean theory, arguing that validating a harmonic system strictly on the basis of simple numeric ratios and the prioritization of consonance seemed inappropriate for the cultural situation they lived in. After a lengthy debate, they agreed that the perfect harmony had to be characterized by a balance between two opposing powers, consonance and dissonance. In accordance to the music of their time, they only saw musical and cultural progress when consonances and dissonances met and interacted in a dynamic fashion. While members of the Sisters of the Harmonic Constellation were typically well-read women, Sieglinde Stern stood out by her unusually advanced knowledge both of traditional weaving techniques and of the most recent developments in the textile industry. An active participant in the group’s discussions, she often used weaving, that is, the integration of two perpendicular systems, the warp and the weft, as metaphors in her interpretations of Plotinus and Pythagoras. In weaving, she would often point out, the weft and the warp can be made of different materials but if one is absent, the fabric falls apart. The Sisters thus sought the musical interval that could best express a balance such as the one present in every woven piece of cloth which leads to its unique quality: firm but also soft. In other words, in response to Pythagoras the SISTERS searched for a single harmony that unites opposites, that is at the same time harmony and dissonance. But which interval has this quality of being a harmony AND a dissonance? The answer was: 7:4. Why 7:4? The 7:4 interval is a minor seventh, but due to the particular tuning of the harmonic series, this seventh is 31 cents flat. In Western Music we are trained to identify a seventh as a dissonance. Dissonances are characterized by a friction and restlessness that ask for resolution. However, the minor seventh has much less friction when it is tuned according to the 7:4 ratio than in any other standard tuning system. Less friction means that from a purely sonic point of view – or also if we apply Helmholtz’ definition of dissonance –, it resembles a consonance. But at the same time, it is still identified as an interval treated in music as a dissonance. The way it incorporates opposing force is what made this interval the unification of consonance and dissonance in the minds of the SISTERS OF THE HARMONIC CONSTELLATION. Let's listen to the difference between the equal temperament 7th, and the justly intoned 7/4 7th. First we hear a cadence in just intonation, that pauses on the 7th, so you can focus on its sonic properties, before it resolves into the tonic. And now we hear the same cadence that remains on the 7/4 7th, without resolving into a consonance. It was in order to reproduce this particular interval and to use it with the Sisters that Sieglinde Stern built the first electroacoustic string instrument – the Di-Cord. Here you can see an authentic reproduction of her instrument, based on detailed documents she left behind. Just as later became common in electric guitars, Sieglinde used a solid body for the instrument, rather than the hollow resonating body that around which all other stringed acoustic instruments had been built up to that time. Because of that, it had a very long ringtime. With acoustic instruments, a lot of the energy contained in the vibration of the string is used up to put the resonating body into vibration, and as a consequence the sustain of a plucked string has a rather limited duration. Sieglinde's solid body instrument, by contrast, didn't have to excite a complex resonating body, and so the energy of the vibrating string dissipated much more slowly, allowing the string to continue vibrating for much longer. The long sustain of her Di-Cord struck the Sisters as having an almost magical quality. On the other hand, the absence of a resonating body also meant that the Di-Cord produced a very soft sound. Today, the same pickup technology is used to shake the walls of buildings, but back then amplifyers and efficient loudspeaker systems had not, yet, been developed, hence it was only possible to amplify the sound minimally, making it unsuitable for public performances with a large audience. Sieglinde Stern's instrument had only two strings, no fingerboard and no frets. Her sole intention in creating it was to produce the 7:4 interval with its eery, otherwordly sound. In addition to plucking, as Sieglinde was an amateur violinist, it is also likely that the instrument was bowed. Sieglinde put her unique instrument to use exclusively with the SISTERS OF THE HARMONIC CONSTELLATION. It became part of a ritual they developed, a sort of meditation where the women sat together, regularly exciting the strings of the instrument and diving with all their attention into its sonic properties. The instrument was simply called the Di-Cord, in reference to Pythagoras' monochord. The design shows a number of interesting details: The length and the maximum width follow a precise 7/4 ratio. You can see two stars that are embossed in the wood, each with the pickup at its center. The stars are a reference to Sieglinde's last name, as Stern in German means star in English, but also to the term "Constellation" which is part of the name of this group. When you look more closely, you will see that one of the stars has 4 spikes and the other one 7, a clear reference to the harmony for which the instrument was designed. In addition, you see a wooden overlay that forms an infinity sign. This was again a reference to Pythagoras' belief in an eternal celestial harmony. On the back of the instrument, the 4- and 7-spiked stars are fused in a single embossed shape, which points at the unification and consolidation of opposites. Back to main page of Why Frets?

|

5. FROM STERN TO STARDUST

Sieglinde Stern passed away in 1859. It would be another nine years before women were admitted at universities. The Sisters of the Harmonic Constellation continued to meet, and use the Di-Cord, until eventually it fell into oblivion. But that was not the end for the pickup. When Sieglinde was in her fifties, she and her partner briefly hosted her distant cousin Johannes Maria August Stroh who had just immigrated from Frankfurt. After arriving in London, he took the name John Stroh. Trained as a clock and watch-maker, Stroh eventually established his own business developing a variety of inventions. His most notable ones were additions to the ABC Telegraph and the Wheatstone Automatic that were the main technologies for telecommunications by the British Post Office. Sieglinde felt a kinship with him, given their shared interest in technology. She must have shared her design for the pickup but it is only twenty years after her death that he first mentioned it, in a 1882 paper entitled "On Attraction and Repulsion due to Sonorous Vibrations, and a Comparison of the Phenomena with those of Magnetism" in the Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers and Electricians. The early 1900s saw the development of the recording industry which, could only employ relatively loud instruments, as microphones were not, yet, developed. Stroh seized on the opportunity, developing the Stroh Violins that made him world famous. However, these and all others of his designs were purely mechanical, and therefore make no use of Sieglinde's invention. Some years later, Stroh's violins attracted the attention of one George Beauchamp, who was on a similar quest to make musical instruments louder. Beauchamp visited Stroh in London in 1914. It is not clear whether he has taken advantage of the declining faculties of the elder Stroh’s, now in his eighties, or whether Stroh was fully aware when he passed on Stern’s design drawings of the pickup. Although the sketches themselves are now lost, Stroh regretfully mentions in one of his last diary entries that an unnamed cousin’s drawings are in Beauchamps possession, now. As I mentioned at the beginning of this lecture, in 1933 Beauchamp incorporated the principle of the pickup in his designs for the electric guitar. However, in none of his writings or patents did he mention that the principle originated in Sieglinde Stern’s designs. And so a woman’s crucial contribution to the history of musical technology was erased from public memory. Sieglinde’s name had another missed connection with fame when David Bowie took on the alter ego Ziggy Stardust in 1972. It is well-known that the character was inspired by Vince Taylor, a rock musician whom excessive drug use had endowed with the belief he was an alien god on earth. What is much less known is that Taylor was a descendant of Mary Taylor, founder of the Sisters of the Harmonic Constellation. In his delirium, Taylor would sometime refer to the organization, of which his own grandmother had been a member. Gathering inspiration whenever he could, Bowie questioned Taylor on the characters that had been part of this constellation, only to hear of a spirit who re-invented music, by the name of Sieglinde Stern. Bowie took a liking to the sound of the name, and modified it into Ziggy Stardust. Supposedly, Sieglinde had red hair. PART III

6. TRANSCENDENTAL TECHNOPHALLACY Over time, the electric guitar became a symbol of Rock ‘n’ Roll and a rebelling youth. Unlike the acoustic guitar, which was played by men and women alike, the electric guitar was almost exclusively played by male musicians. Led by such towering figures as as Chuck Berry or Jimi Hendrix, it was turned into a sexualized symbol of male potency. The instrument became the most iconic phallic symbol and an embodiment of electric sound, a symbolism that probably reached its apex when Prince made it ejaculate. The symbolism took a life of its own in the practice of Air Guitar, which Steve Waksman refers to as "transcendental technophallacy". Air Guitar isolated and exaggerated the chauvinistic gesture while paradoxically performing self-castration by relinquishing the materiality of the instrument itself. Waksman argues that the performance practice of electric guitar led to the extinction of the instrument by giving an increasingly prominent place to the male postures and gestures, eventually overcoming the corporeality of the instrument, in a process he called transcendental technophallacy. For Waksman, despite the disappearance of the guitar as a physical object, it became eternal in the minds of its followers, imbued with a god-like status, while the player acted as a priest. However, a better interpretation was offered by Varga Takács, when he introduced the so-called “species-turn” in the genealogy of instruments. This theoretical approach, which I will be following in my last comments, suggest the exact opposite: For Takács, rather than dissolving the guitar’s corporeality through Air Guitar, what eventually led to the guitar's demise was the maximalization of the guitar's materiality. 7. REQUIEM XX33

As I begin to wrap up this presentation, let’s notice the importance of the number 33 throughout this history. In 1733 John Kay invented the flying shuttle, which, served as a model when Stern invented the first electro-magnetic pickup in 1833. George Beauchamp then used it in the first electric guitar in 1933. Today, we are in the year 2083, another 150 years later. Where do things stand now with the electric guitar? As is well known, the year 2033 – once more the number 33! – saw the final public performance with an electric guitar, namely of Thurston Moore, whose earlier work with Sonic Youth had already redefined rock music through a variety of experimental practices that influenced the New York Downtown scene of the 1980s. Since then, the electric guitar has been all but abandoned from public performances. This demise can be explained by using Varga Takács’ theoretical species-framework. Contrary to Waksman's Transcendental Technophallacy, this approach centers not so much on Air Guitar, and the dissolution of its corporeality, but rather on a maximization of the electric guitar’s materiality. As is well known, the metal genre celebrated the guitar as a tool to display chauvinism. In order to match the tonal register of the metal growl, metal musicians soon decided that 6 strings didn’t suffice anymore - it had to go lower! So at first a 7th string was added, then a 8th, a 9th, a 10th, an 11th and ...well you can guess where this is going... ... strings were added until the instrument became unplayable. According to Varga Takacs' species-framework, the electric guitar suffered a similar destiny as that of the Irish Deer. The Irish Deer became extinct around 7700 year ago. This was the result of a gradual growth of the animal antlers, through sexual selection. Every generation of male Irish Deer kept growing larger and larger antlers, a powerful symbol of strength and potency that eventually proved a crucial handicap when being chased through the woods by hunters, in addition to creating a nutritional burden. Over time, this led to the extinction of this species. According to Tákacs, a similar ‘Maladaptation’ led to the end of the electric guitar. However, here we find something remarkable!: The growing number of parallel strings in the last models of electric guitars shows a striking resemblance with the parallel wefts of a hand loom. And so if you will allow me to drift away from the strictest methodological standards to close this talk, I would dare to speculate that at the very end of the electric guitar’s lifespan it finally revealed its repressed origin. Like a guilty conscience ignored for too long, two hundred years later the mark of Sieglinde Stern finally became visible, symbolized by the craft that inspired her in the first place: the art of weaving. Credits

This project has been produced and made possible by ChampdAction, Antwerp and the ORF (Musikprotokoll). It has been funded by the SKE-Fund, Austrian Bundesministerium, and Land Steiermark. It is supported by the Kunstuniversität Graz. |